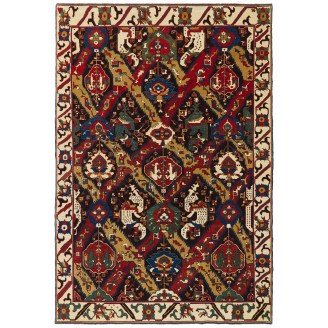

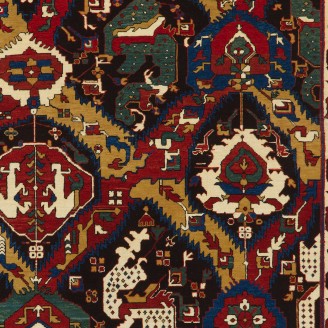

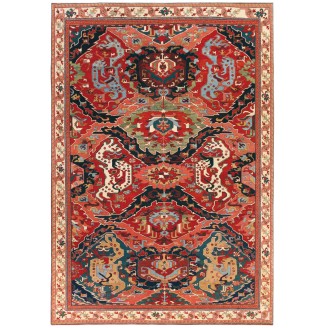

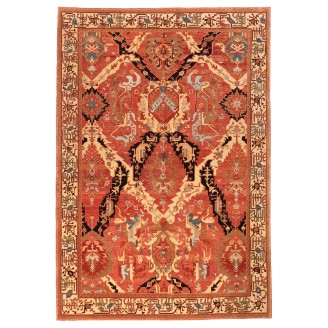

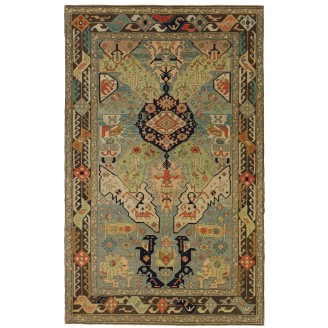

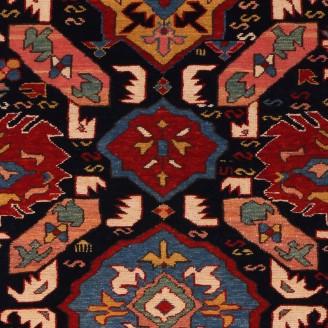

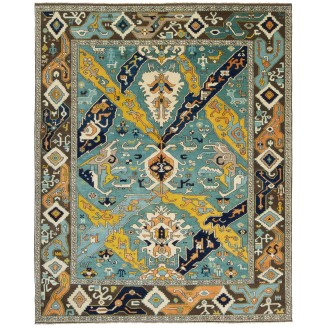

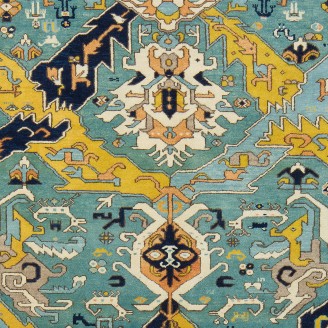

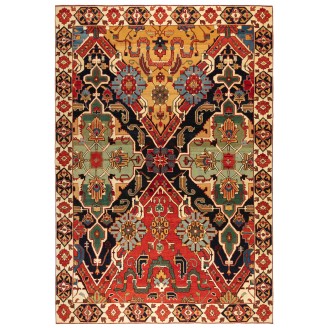

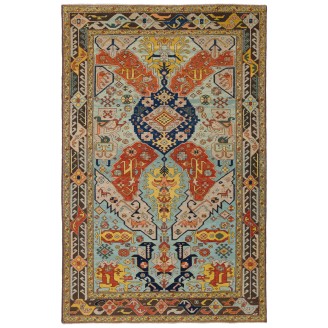

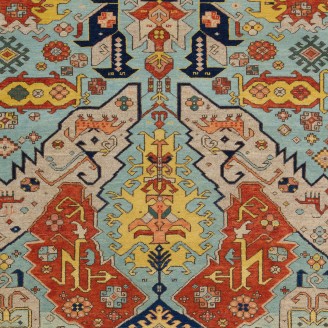

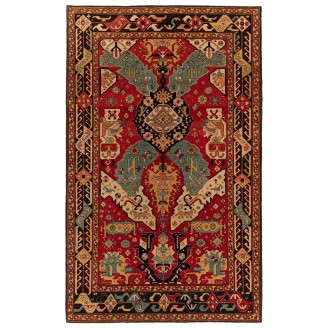

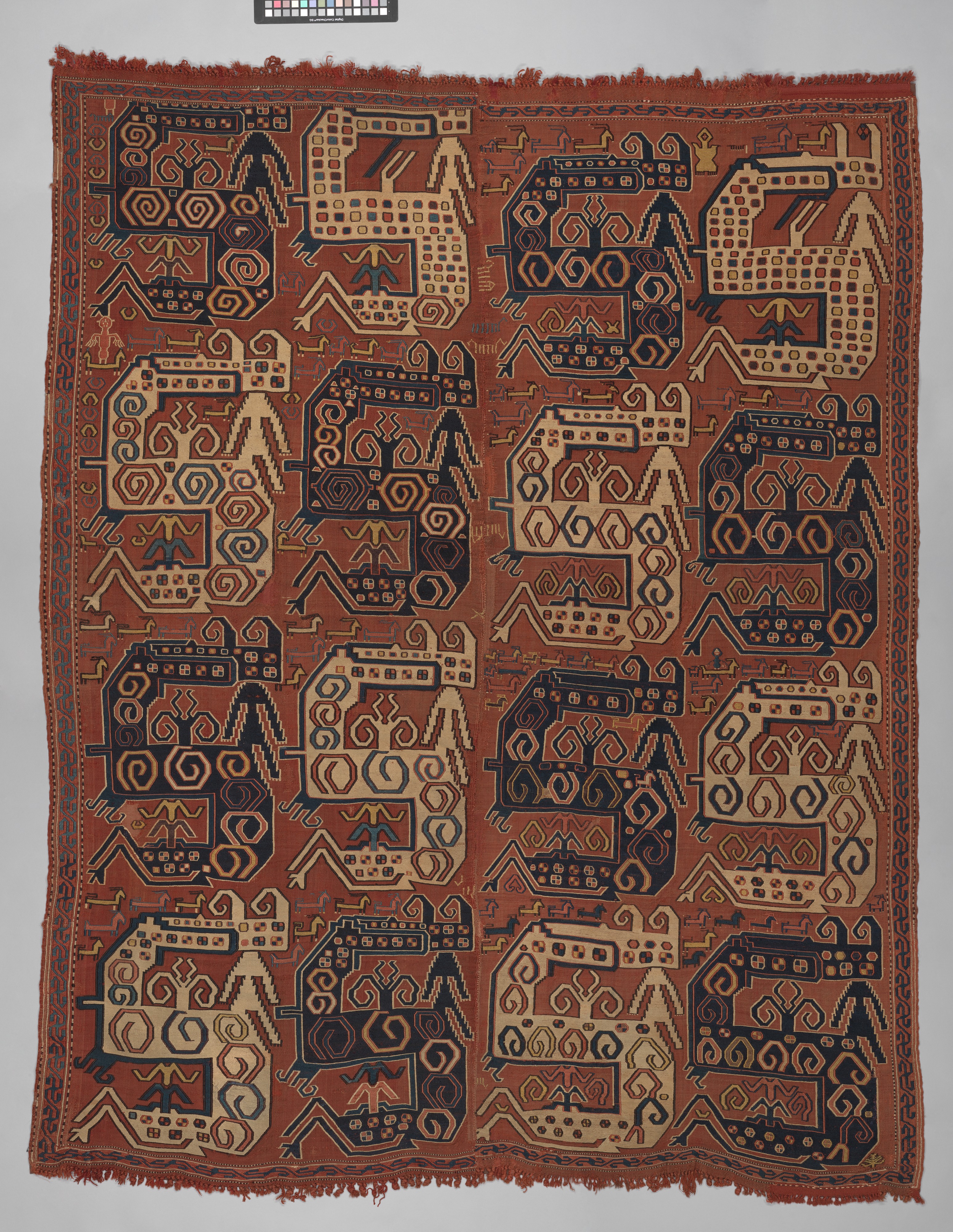

No rug from the Caucasus bears the hallmark of so-called "court-weaving," that is, the corners of the borders are not carefully drawn to secure continuity of pattern, but the monumental scale of design and the large size of the early pieces puts them among the most exciting rugs ever made and assures them of a place in the tradition. The first and best-known are the "Dragon Rugs." They present what has been deemed the most energetic form of decoration ever placed within the confines of a woven fabric. They are followed by the rare trellis rugs, such as the "Niğde Carpet" in our collection, and by a group in a large, assured, bold scale generally known as "Kubas." A third early type seems to be patterned on the great Persian hunting carpets of the 16th century but is drawn with an extraordinary sense of abstraction. A fourth style repeats a wide palette of crisply drawn palmettes and rosettes and a frank imitation of a Persian medallion carpet remind us of the close connection, at this period, between Persia and the Caucasus.

Rugs Merchand from the Caucasus (19th Century)

Rugs Merchand from the Caucasus (19th Century)The history of the Caucasus has been one of constant turmoil. Sited at the meeting point of two worlds whose civilizations had no common ground, this area was always the principal objective in their thirst for expansion. In the distant past, hordes of invaders-Cimmerians and Scythians-bore down from the Eurasiatic steppes. The Greeks and Romans, who discovered a land and climate similar to their own in the Transcaucasus, infiltrated via the Bosporus. Later still, Persia and Byzantium vied for control over this passageway between the East and the West. The two kingdoms of Armenia and Georgia were born amid this turbulence. Their prosperous development between the eighth and the twelfth centuries allowed them to refine their culture and to weld their unity in anticipation of the attacks to which they were subjected. And in their turn, Arabs, Seljuk Turks, the Mongols of Genghis Khan, and Tamerlane did indeed perpetrate murderous assaults upon them. After the fall of Constantinople, which isolated the two kingdoms from the rest of the Christian world, Persians and Turks of the Ottoman Empire took up the charge again and fought over the Transcaucasus, a fruitful land with easy access. When the Russians seized the Caucasus, they were to discover the contributions of foreign civilizations left there by the innumerable invaders and ultimately blended into the original culture.

The oriental imagination is given free rein when designing a rug, for there are indeed an infinite variety of patterns. In the beginning, each motif possessed its significance, transmitted from generation to generation. But very often, with time, these meanings were lost.

The Caucasian rug, with its predominantly geometric designs, might seem to be the expression of primitive art. In reality, it reveals amazing inventive talent coupled with remarkable maturity. The strict rules governing iconography have never restricted or slowed down the impetus of carpet design. The patterns exhibit highly successful stylization and express great charm with rather simple motifs consisting of figures, animals, flowers, stars, squares, and lozenges, depicted quite diagrammatically and frequently positioned without attention to symmetry. Flowers do not play as essential a role on Caucasian carpets as they do on the carpets of Iran or India. They figure in the borders or complement other geometric motifs by providing the central feature or frame; often, they are treated in a stylized fashion similar to the other.

Caucasian Patterns

Caucasian Patterns Dragon Carpet, late 18th century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Dragon Carpet, late 18th century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkThe particular charm of Caucasian rugs lies in the beauty of their colors and the harmony of their dye combinations. The dyers, well-versed in the preparation of their materials, manage to obtain warm, deep tones, both brilliant and discreet; moreover, with their keen awareness of the interplay between colors, harmony, or contrast-they succeed in creating stunningly expressive effects. In the Caucasus, green, a color rarely found in carpets from other regions of the East, is used very often.

In the nineteenth century, knotting was at its height in villages and among nomadic tribes. The introduction of chemical dyes happened more slowly there than elsewhere; until the present century, villagers and nomads preferred to work with natural colorants, handing down the formulae from generation to generation. Chemical dyes (although known since 1865) were adopted very slowly, and then not in every region. Without thorough analysis, it is now difficult to determine the particular colorants used in dyeing a carpet. The earliest synthetic dyes were of poor quality. They faded in the sun or artificial light and lacked the shimmering luminosity that radiates from carpets with natural dyes. One easy way to establish the type of colorant used is to spread apart the pile to check whether the dye is consistent at the base and the end of the strand. If a difference is discernible, the dye is almost certainly synthetic. However, some natural colors also fade (in cases where the mordant was of poor quality)

Most of the rugs of the Caucasus are knotted in the Turkish manner with a symmetrical knot, also called the Ghiordes knot. This knot is tied on two adjacent threads of the warp, each encircled by the strand of yarn, the ends of which emerge between the two warp threads. After each knot, the weaver cuts the wool and operates on the next two warp threads. Two shoots of weft are then passed right across the warp, the first through one warp level and then, as the sheet is reversed, beneath it to support the knot and ensure the firm structure of the rug. The pile is formed by these knots, which are cut and clipped to a uniform height. Most Caucasian carpets are constructed with a depressed warp. Therefore, part of each knot is hidden. Only some types of Kazak and Shirvan rugs have the warp on one level; in these, the knot is obvious on the reverse of the carpet.

Photo: Anatolian Rug Weaving, 2021 Gaziantep

Photo: Anatolian Rug Weaving, 2021 Gaziantep